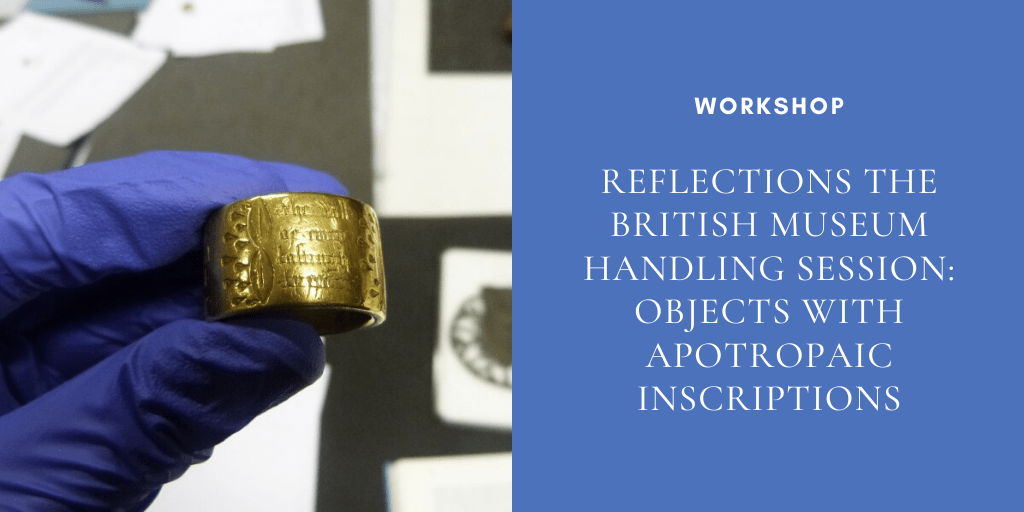

The Courtauld has a reputation for getting up close to objects, sometimes to the concern of nearby gallery attendants. However, a number of handling sessions for postgraduate students to indulge in pawing exhibits without rebuke have been arranged at the British Museum with the kind assistance of Lloyd DeBeer and Naomi Speakman, both in progress with individual collaborative PhDs at the Museum. The theme for this December session was objects with apotropaic inscriptions, that is, words that apparently warded off evil, as requested and selected by Dr. Tom Nickson.

As we gathered round the table, putting on our unpleasant plastic gloves, what could not fail to draw attention was the impressive (and perhaps also apotropaic) axe-carved prow ornament under conservation for the forthcoming Viking exhibition. However the objects we were to be handling lay beyond this fearsome monster, and were of a much more manageable weight.

This bell was my first port of call, partly being the second biggest thing on the table after the prow, but also because I had just written about bell-founding through the lost wax method with my post on Courtauld favourite Tudor Monastery Farm. Bells are one of the most common medieval objects to be inscribed with the craftsman’s signature, but this one also had four holy figures inscribed upon it which perhaps were there to protect the bell, while the former maybe acting as a perpetual prayer to the maker. Handling a bell like this immediately gives you the impression that it is far too heavy to ring by hand. Instead, the shape of its upper aperture was suggested as perfect for it to be attached to a wooden frame, and rung by a mechanism. Although there were a few accidental semi-peels, we of course were not going to see if one could bear to have this bell hung low enough to be reminded of its maker while sounding the call to prayer.

One object that proved particularly popular was this French fifteenth-century finger ring, inscribed with an amorous inscription playing on Latin tenses. This blog is possibly not far from the truth in that it represents a particularly nerdy love-token: the image of the squirrel and lady on the inside being a not-so-subtle medieval double-entendré.

However, that ring represented an object that matched our expectations, ideally sized to be placed upon a lady’s finger for her to cringe at the grammar puns forever more. My personal favourite object of the day was the Coventry Ring, both for its content and the puzzles its actual presence made manifest. On the outside, we have an image of Christ, and a prayer that relates to each of His five wounds. This prayer is accompanied by the characteristic disembodied floating sharply-pointed ovoids dripping blood, which, after Caroline Walker Bynum and others’ in-depth investigations of textual and iconographic parallels for the femininity of Christological imagery and devotion, you are allowed to state the obvious resemblance without the risk of getting too Freudian. This prayer is obviously supposed to be read while the ring is turned around the finger, but even this does not explain why it is so conspicuously large when you try it on. Was it made to commission for a particularly big man? Was it designed to be worn over a leather glove? Was it even supposed to be worn other than for prayer? The startling condition of the ring, even the enamelling of lettering inside and out, suggests perhaps so.

These are just a few of the thoughtful fruits that were generated from handling the objects set out for us. But perhaps what never really came out were many opinions about the apotropaic inscriptions which they all had in common. The Coventry Ring was one of many of the objects that had the names of the Three Magi inscribed upon it for instance, clearly from some common mystical significance. Yet so often the more mysterious and magical inscriptions were sidelined in our discussions for other, seemingly more primary functions that the objects embodied. Perhaps it was the same for their users: these were merely conventions that it was proper to have, and even the owner of the Coventry Ring themselves may have been hard-pressed to explain what “ananyzapta tetragrammaton” was all about.

Here is a list of the objects we had out and a link to their catalogue entry:

Laureate head pendant

Late Medieval Bell, English

The Hockley Pendant

The Coventry Ring

Cameo/Amulet ring, Italian, C14 (no image)

Amulet ring, Italian, C14

Annular Broach, English, C13

Finger ring, C15

Pilgrim badge of Henry VI

Mould for similar Henry VI badge

Thomas Becket pilgrim ampulla

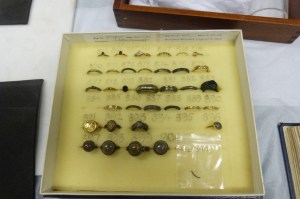

We also had a large box of rings of lesser interest out.

These included:

1856,0701.2707, 1856,0721.1, 1858,0628.1, 1865,1203.34, 1872,0604.379, ML.3995, OA.7467